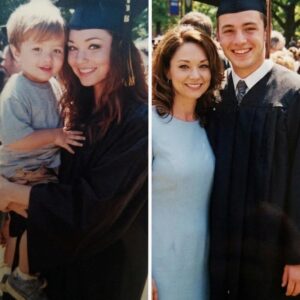

After five miscarriages and years of quiet grief, the narrator was nearly broken when a doctor suggested she accept that her body might never “cooperate.” Alone on a bathroom floor, she prayed out loud for the first time: if God gave her a child, she promised she would “save one too” by adopting. Ten months later, Stephanie arrived—loud, healthy, and miraculous—and the narrator felt both joy and the weight of that vow. On Stephanie’s first birthday, she and her husband signed adoption papers, and two weeks later they brought home Ruth, an abandoned newborn. The girls grew up knowing Ruth was adopted, and their mother loved them fiercely and equally, yet their differences sharpened with age: Stephanie was bold and attention-grabbing, Ruth careful and watchful, always measuring whether she truly belonged. As teenagers, small rivalries became painful fights, and underneath them ran a deeper fear Ruth couldn’t name.

The fracture came the night before prom, when Ruth—shaking with anger—said she was leaving and accused her mother of adopting her only to “pay” for Stephanie. Stephanie had overheard the old prayer and used it as a weapon in a fight, twisting it into proof that Ruth was a transaction. The mother tried to explain the truth: the vow didn’t create her love, it revealed how much love she had left to give. But Ruth, already wounded, left anyway, and the house filled with regret. Days later she returned, exhausted and raw, saying, “I don’t want to be your promise. I just want to be your daughter.” Her mother held her tight and answered the only thing that mattered: she always was. In the end, the story isn’t about biology or bargains—it’s about a child needing to be chosen for herself, and a mother learning that love must be spoken plainly, not assumed.